Like millions of other devotees, I was glued to my television to witness the most recent episode of HBO’s astoundingly popular Game of Thrones. I love the show, even when its characters annoy me, and “The Battle of the Bastards” (Season 6, episode 9) promised to feature an epic medieval battle.

Since I’m a medieval military historian as part of my day job, this means that my viewing of the episode constituted “research,” and that I have quite a few thoughts about just how medieval the Battle of the Bastards (BoB) really was. In discussing my reactions, it should go without saying that SPOILERS abound for the episode. Also, some of this is a bit graphic. You’ve been warned.

During the after-show interviews that aired on HBO, Game of Thrones producers Dan Weiss and David Benioff—who co-wrote the script for this episode—stated that they indeed wanted a big “medieval” battle, and that they based the BoB sequence on the historical Battle of Cannae. This is odd, to say the least, since the Middle Ages roughly date from 500 to 1500 CE, whereas the Battle of Cannae occurred on 2 August 216 BCE—seven centuries before we get to the medieval period. Miguel Sapochnik, the director of the episode, has subsequently filled in that rather wide gap. In an interview with Entertainment Weekly, he says

Initially we based BoB on the battle of Agincourt which took place between the French and English in 1415. But as needs changed, as did budgets, it became more like the battle of Cannae between the Romans and Hannibal in 216 BC.

In other words, BoB is an ancient battle fought with medieval military technologies.

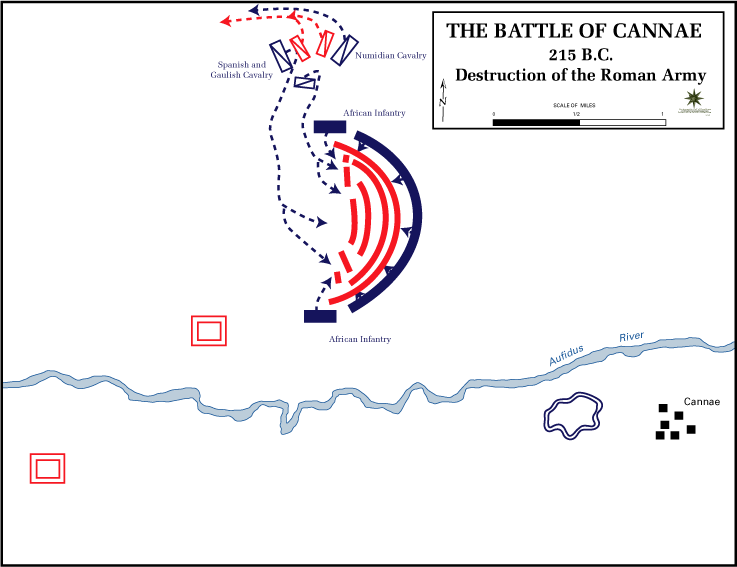

The correspondence between BoB and Cannae revolves around the primary battle plan: to envelop the opposing force and crush it. At Cannae, Hannibal had brought his Carthaginian forces down from the “wall” of the Alps (his path through them, long a mystery, may have recently been found) and had been ravaging the Italian countryside for two years when he was met by a Roman army on the plain beside the Aufidus River, about 14km west of the coastal city of Barletta today. Hannibal was outnumbered: ancient sources report he had perhaps 50,000 men and was opposed by more than 86,000. While these are inflated numbers, to be sure—such accounts are notoriously unreliable when it comes to accounting—the general proportion of the armies in the field is probably roughly accurate.

The armies at Cannae formed up as parallel lines, but when the Romans surged forward into them, the Carthaginian center was pushed or fell back. Whether or not this action was deliberate or just dumb luck after the fact has long been debated among scholars. One’s answer, perhaps not surprisingly, generally depends on what one thinks of Hannibal’s brilliance as a military strategist. Regardless, the Romans pressed their advance and as the Carthaginian flanks held while the center receded, Hannibal’s lines bent into a great crescent and then, at last, held their ground. Though for a moment they had surely thought they would drive Hannibal in flight from the field—which was and is the desired outcome of a battle, since it allows one to cut down the panicked and fleeing opponent with relative ease—the Romans now found themselves surrounded by him on three sides. And when Hannibal ordered his flanks to press forward, the Romans were further packed in until they were encircled and slaughtered.

It is this same tactic, called a pincer movement, that Jon Snow and his Team Stark war council intended to unleash upon Ramsay Bolton’s larger forces in BoB: like Hannibal, they planned to use their enemy’s superior numbers against him. Hemmed in, those numbers would crowd and impede one another. And the results would have been catastrophic for the Boltons.

The fact that the Starks instead ended up on the receiving end of this same kind of pincer movement is a testament both to Ramsay’s cunning and Jon’s imbecility as a leader. (Seriously, not only did Jon abandon his plan completely, but he failed to give any directions or orders once he did; it was a total Leeroy Jenkins, which never goes down in the annals of great leadership.)

In terms of reality, we might say so far so good: the tactics in BoB are known from history, and the way that Benioff and Weiss flipped the script on the predictive outcome was rather clever.

There were also some great moments of realism within the action on screen. I would be hard-pressed to think of a better sequence at capturing the horrible chaos of medieval battle. I applaud Sapochnik for keeping the camera in the thick of the tumult with Jon rather than going for the grand panoramic shot as directors often do. It was a brilliant decision that left me riveted as a medievalist.

Indeed, throughout that intense sequence I kept thinking of the Battle of Crécy, one of the most famous battles of the Hundred Years’ War. We have a few eyewitness accounts of that battle, including that of an anonymous fighter from the Low Countries, who wrote of what he saw:

Men hunted there all so bitterly;

No man wished to give way to the other;

Men split many a helmet,

so that the entire brain and blood

out of the head must fall.

Of the bitter battle we cannot describe,

For it was so horrible and so ghastly.

Eight helmets sprang from four.

Many bodies were struck down,

So that the intestines spilled out;

Men hewed off arms and legs

in the terrible chaos of battle.

Soldiers trampled many under foot,

Who nevermore rose again nor stood.

They came to a heap on both sides.

No one could avoid the other;

Men fought bitterly forward and back.

The sword went up and down.

Each slew there another lord;

The horses leapt all asunder.

The screams and shouts were so great

That they frightened even the dead,

To there many men were sent.

No affair had ever been so bitter;

Those killed and those wounded,

Their blood leapt there like rivers:

It was horrible to see.(“Rhyming Chronicle,” trans. Kelly DeVries)

The terror and the tumult that I saw in BoB captured the trauma of this experience better than anything I have seen. And it went even further, as Jon finds himself trampled by the living and nearly buried by the dead, an awful truth of medieval conflicts. Another man who survived the Battle of Crécy, for instance, was the herald Colins of Beaumont. In his own poem recounting the tragedy of the battle, he writes of living men still being pulled from the likes of corpses strewn upon the field … three days after the fighting was done.

So there was much in BoB that I liked as a medievalist, much that rang true.

Alas, not everything did.

Take, for instance, the armoring of the men involved. The average ten-year-old knows you shouldn’t ride a bike without a helmet, but apparently no one of any importance on either side—not Jon, not Ramsay, not Ser Davos, Tormund, Wun-Wun, or anyone else I can think of—has heard about this potentially life-saving invention. It’s astounding. And sure, I know the director wants us to be able to recognize Jon in the fighting, but there’s got to be a way to do this that doesn’t make him look like a bloody fool. For crying out loud, folks, if you can’t think to put a helmet on before entering a medieval melee, you’re a dead man walking (rimshot).

Another problem was Ramsay ordering his archers to shoot indiscriminately on his own men in order to pile up the dead. I suppose the notion the writers had was to show us how evil this particular bastard is, but as an audience we have long known that Ramsay is the moral equivalent of a dumpster fire behind the downtown Denny’s. We didn’t need the reminder.

Besides which, it’s an entirely irrational and ahistorical act: who would subsequently follow a man who so carelessly tosses away the lives of his followers? As Kelly DeVries points out, it’s simply unheard of. Such a leader would awake in chains or worse. It’s not as if the world of Westeros follows a theocratic regime of divine right of kingship that might (but still probably not) convince men to skip to their deaths so readily. Here, I suspect the show’s creative team wasn’t inspired so much by history (nothing like it happens at Cannae, Agincourt, or any other battle they’re likely to know) as by the movies: a strikingly parallel scene occurs in Mel Gibson’s Braveheart. There, it is the wicked English King Edward I who orders his archers to loose on the massed melee during a very, um, creative version of the Battle of Falkirk. When one of his officers points out that they’ll hit their own soldiers, King Edward (Patrick McGoohan) turns to him and says “Yes, but we’ll hit theirs, as well. We have reserves. Attack!” (Watch here, starting at 4:00 mark.)

I’ll grant that Braveheart might be a fun movie, but it sure isn’t history, folks. The Battle of Stirling Bridge ought to have involved both a bridge and a river. There was no prima nocte (“first night”) practice. Isabella, the French-born princess who falls in love with Gibson’s William Wallace was only nine years old when he died and still living in France. And oh gods the fact that all the Scots are in plaids … well, suffice it to say that when it comes to history Braveheart is almost as loony as Gibson has sometimes been.

So BoB had some fantastic medieval elements, and it had some elements that were just plain fantastical. Of course we can’t expect a fantasy to match reality. And I well understand the need to add creative twists for dramatic effect. In my novel The Shards of Heaven, for instance, I retold the naval Battle of Actium between the forces of the future Augustus Caesar and those of Antony and Cleopatra. It’s very likely that in real-life the sun was shining that day, but I thought it more interesting for my historical fantasy to put it in storm. Plus, the Trident of Poseidon probably didn’t take part in the fight. More’s the pity, I think.

In truth, as creative artists we are constantly walking the line between reality and imagination, and it is up to our audience how far they are willing to follow us from the known comfort of one into the unknown wonder of the other. Despite the historical oddities of this last episode, I for one am willing to keep following these particular creative artists once more into the breach.

So keep it up, HBO. Give us more quasi-medieval battles!

But, seriously, for the sake of humanity, let Jon borrow a damn helmet next time, okay?

Michael Livingston is a Professor of Medieval Literature at The Citadel who has written extensively both on medieval history and on modern medievalism. The Gates of Hell, the second volume in The Shards of Heaven, his historical fantasy series set in Ancient Rome, comes out this fall from Tor Books.

I’m sure it could be chalked up to arrogance, but does Ramsay have no scouts ANYWHERE? Who allows an entire cavalry host – which has ridden from hundreds of miles away – to sneak up behind them in theoretically friendly territory? They can’t have been more than ten miles away when the battle began. Classic Bolton mismanagement.

That’s interesting about the arrows. Would it really be inconceivable for a ruler to make the calculation that killing roughly equal numbers of their own and the enemy’s men from indiscriminate arrow fire would be helpful?

Ramsay really is on the far-extreme psychotic end of the spectrum even in his very brutal environment. It does strain disbelief a bit that people follow him at all, given how much of an obvious monster he is. But he does have the official authority of the realm behind him, and can be counted on to do unbelievably terrible things to the first traitor or deserter, so I guess I buy it.

Fear of Ramsay still doesn’t account for NOT A SINGLE BOLTON SOLDIER PANICKING AT THE SIGHT OF A GIANT. Or at the sight of said giant snapping a man in two with his bare hands.

That said, I have no idea why Wun Wun wasn’t wielding an entire tree as a club, or just trampling over pikemen when they got surrounded, instead of just grabbing one.

“…but he failed to give any directions or orders once he did; it was a total Leeroy Jenkins, which never goes down in the annals of great leadership.)”

Quite possible hannibal and any other leader never did anything of value in a battle either, we can’t know that. The winner of the battle can always rewrite what happened any way they want.

who would subsequently follow a man who so carelessly tosses away the lives of his followers?

French knights rode down and slaughtered their own crossbowmen (hired Italian mercenaries) at Crecy. Class and ethnic differences made that a bit more palatable, though.

@@@@@ Alex Harrison – at Waterloo, Napoleon had an entire Corps out looking for the Prussians, yet, surprise, surprise, the Prussians showed up at the most inopportune time.

Thank you Michael!

I’m surprised you and others did point out the oddness of the piled bodies. Yes, Ramsey wanted to up the death count to create a pile, but having even 4000 men fall in the same place while climbing on top of each other seems as bad of a sin as the Stark army fighting without helmets.

Yes the men were dying in the same general area, but the massive pile seemed to come out of no where.

Ramsey sitting there with only 2 men – another general and the banner man. Eyeroll.

And I agree with @3.

Giant = panic. Giant = smash the spearheads.

But it was an amazing thing to watch from my TV.

@3. I agree. Terrible use of strategic resources by Team Stark.

@@.-@. I like Jon, and Kit Harrington’s performance was amazing. But he’s the opposite of a leader in this one. Here’s hoping he gets his act together when the White Walkers stop walking in circles and head south.

@5. If you check out my recent Battle of Crécy: A Casebook, you’ll see that the French intentionally riding over the Genoese is a myth. The truth is far more interesting (and understandable).

@6. True enough, though the geographical scales were far larger there. The Knights of the Vale ride right up to the foregrounds of Winterfell without encountering scouts or pickets or informants of any kind. While it was predictable in the show, it is laughably preposterous against history.

@7. It was indeed sudden. They were thinking of the body walls in the Civil War, I’m sure, but that’s of course a gunpowder conflict. And yeah, the “staff” around Ramsay was silly.

The helmets, though … it’s something that bothers me a lot. You’ll see it mentioned again in my medieval review of the Warcraft movie when it comes out. ;)

I watched this episode with my parents. My mother immediately questioned why Ramsay would shoot at his own men. I replied that it was because they’ll hit just as many of Jon’s men…and I was immediately reminded of the scene in Braveheart. My father remembered it, too. But my mother hushed us before we could get into the great discussion of that movie’s rampant inaccuracies.

@9 RE: Helmets

I’ve heard many directors and producers say that they simply can’t have the leads in helmets. Its not even about identifying them, as much as it is featuring their good looking faces, and all that hair. Its the movies, after all. I don’t remember Aragorn or Eomer in helmets, either. Gimli wore one, though.

I thought the Bolton soldiers charging into the fray were going to turn on Ramsey when they slowed before clashing, similar to the conscripted Irish in one of the battles in Braveheart. That would have been a more satisfying end result than Baelish’s forces appearing.

The “no helmet” thing is no different than cop shows. The main characters, never wearing more than a vest, enter buildings with or even leading the heavily-armored SWAT team. Why they haven’t all gotten their heads blown off is a mystery. Maybe because the bad guys always aim for the vest.

Television and Film are particular mediums in which obscuring the faces of your actors is, unless it serves a particular purpose., universally bad. The audience needs to know who is who, and they need to be able to place people they care about within the context of the action, or it all just becomes an empty, some-what boring blur. How much did anyone care about any individual Bolton getting mowed down by the Knight of the Vale? Or any individual north-man or Wildling caught in the crush of the shield-wall. It’s a sacrifice of historical accuracy to narrative necessity, which is something that happens in plenty of other instances. In visual storytelling, putting something between the eyes of the actor and your audience induces distance. Obscuring the face more-so.

Did the shield wall battle look realisitc to you? I thought shield walls were more about pushing and people opportunistically killing each other where they met. Weren’t the Bolton spears too long for what they intended?

As epic, satisfying and fun this episode was, my main gripe was Wun Wun’s lack of weaponry. In the books, the giants are said to fight with tree trunks with rocks and other things tied to them. Had he used anything like that, he could have taken out half the Bolton’s himself. Either G.R.R.M. messed that up, or the show creators did, as it wouldn’t have been fair with Wun Wun laying waste to the army… and maybe that’s why it was done the way it was.

Great breakdown, Michael!

Given that the Bolton forces should have known by now that there was a giant traipsing around the area, mayhaps they could have shown they disabled Wun Wun somehow, so he could be out of commission, but still be part of the actual taking of the keep.

I loved this episode so much for its cinematography, intensity and tone but yeah, on a strategy and tactics level it’s pretty bad. First of all, why don’t the Umber’s rule all of Westeros? They seem to be about the only people in the land with the combination of shields, armor and spears. If they don’t get hit in the rear by cavalry, they could concur all.

Two, does no one have any intelligence agents? Where are the Ravens? “My Lord Bolton, a force from the Vale has taken Moat Cailin.” “My Lord Bolton, a large army of heavy cavalry flying the banners of Aryn has passed our position heading in the direction of Winterfell.” That’s all it would have taken.

I have many other issues but I’m going to let it all slide. Why? Because that brief overhead shot of the Vale cavalry hitting the Umber’s rear was freaking amazing. Made it all worth it for me.

Helmets with face visors produce the same problem for both military and television affairs – a supreme difficulty in identifying the person inside the iron mask. The military solution was heraldry for long-range identification and communication, and movable visors for short-range purposes.

As for the body pile-up, that kind of corpse wall could occur, as at Agincourt, but only if the field of engagement were restrictive, as at Agincourt, forcing the combatants to clamber over casualties to continue to fight. Otherwise, they would simply move around the fallen and not chance the uncertain footing of stepping on a body.

Excellent review! I agreed with pretty much everything that you said. I could overlook some of the inconsistencies because of how EPIC the battle was but I still had the same issues some of you had. Here are just 3 of them:

1. Knowing there is a giant amongst your foe and SEEING a living, breathing one is very different. If I can quote Negan here, it would be “pee-pee city.”

2. Poor Wun-wun, he obviously did not learn how to fight very well over The Wall. Knowing he is the biggest thing around and would therefore make a huge target- no shield or helmet? And yes, a huge tree as a club would have decimated the Bolton forces.

3. Firing arrows into EVERYONE should have made his tenuous alliance break: either retreating or turning on him. Which is what I was still hoping for with the freaking Umbers.

If the Starks remain as rulers of the North, there is going to be a huge change in “Houses.” I now see House Umber as House “Tormund” or “Giantsbane.”

Again, thanks for the great review. Elise Tobler sent me here and I’m glad she did!

House Giantsbane sounds pretty cool, although I’ve always wondered what Wun Wun thought about one of his closest friends having that last/nickname.

@11 – I think you’re right about Aragorn, but Eomer (and Théoden) did wear helmets. Eomer wore one at least in the scene where he’s introduced (the Rohirrim circling Aragorn, Gimli, and Legolas). I haven’t watched recently enough to recall whether he wears it during the Ride of the Rohirrim/Battle of the Pelennor Fields. Théoden definitely wore one during the latter.

@21 In the books Tormund tells the story behind that nickname and it’s much friendly to giants (according to him he should’ve been named giantsbabe lol). Wun Wun would’ve no problem with that story. But the show cut that awesome story along with Tormund’s brand of humor.

Thanks for this analysis. I am always interested in the historical precedents that authors use for their fictional battles.

The lack of helmets is the fantasy version of those movie spacesuit helmets that have lights in them pointed at the actor’s faces, so you can see their faces. In the real world, who would want lights INSIDE their helmet?

Bolton infantry seemed to me a curious mixture of phalanx spears and pre-Marius legionary shields. Not much medieval in sight. But as pictured the phalanx actually would be vulnerable to cavalry, might not be able to avoid being flanked.

I watch GoT for the costumes, in any case. As presented so far, there is no story being told. And even Arya is becoming despicable.

I thought the episodes was awesome, when I was watching it I loved the scenes with Jon and the corpses piling, they were almost suffocating! Pity for the cringe-worthy lack of helmets, but Jon didn’t get trampled to death (Melisandre was away after all) at least. I really love it when, as you say, creators walk the line between reality and imagination in a truly satisfying manner for their audience.

@@@@@ 25 – Re: Arya Stark.. Um, the season finale tonight? Make sure you’re sitting down.

@23 – Ryamano: Oh, he’s the one who claims to have nursed on a giantess, right.

I’ve yet to see anyone anywhere recognize the most strategically egregious mistake made by either side. Yes, Wun Wun should wield a weapon. Rickon should zig. Jon should not be allowed to make decisions. But once Ramsey succeeds in baiting Jon to charge at him well ahead of his forces, all alone, why, oh, why would he ever bring down his horse. If your opposing commander is delivering himself to your feet, don’t stop him the charge out to meet him. Let him arrive, fill him with arrows point blank, and watch his deflated followers melt away into the woods. The rhythm of strategic blunders was like watching the Packers surrender an insurmountable lead to the Seahawks in the NFC championships a few years back. the strategic blunders were so bad I switched whom I was rooting for.